Assignment - 1 - Tagore’s New Woman Relocating the “World in Her Home”

TOPIC OF THE BLOG:-

This blog is part of an assignment for the Paper 201 - Indian English Literature - Pre-Independence - Sem - 3, 2024.

Tagore’s New Woman Relocating the “World in Her Home”

Table of Contents:-

- Personal Information

- Assignment Details

- Abstract

- Keywords

- Introduction

- Background and Overview of ‘The Home and The World’

- New Woman Ideology

- Character Analysis

- Bimala

- Nikhil

- Sandip

- Themes of Tradition and Progress

- Conclusion

- Works Cited

Personal Information:-

Name:- Nanda Chavada N.

Batch:- M.A. Sem 3 (2024-2025)

Enrollment Number:-5108230012

E-mail Address:- nandachavada@gmail.com

Roll Number:- 19

Assignment Details:-

Topic:- Tagore’s New Woman Relocating the “World in Her Home”

Subject Code & Paper:- 22406 - Paper 201 - Indian English Literature – Pre-Independence

Submitted to:- Smt. Sujata Binoy Gardi, Department of English, MKBU, Bhavnagar

Date of Submission:- 20 - November -2024

About Assignment : This assignment examines Rabindranath Tagore's portrayal of the "New Woman" through Bimala in Ghare-Baire, highlighting Tagore's progressive views on female identity, autonomy, and empowerment within the societal shifts of early 20th-century Bengal.

Abstract

This Assignment explores Rabindranath Tagore's portrayal of women, particularly through the character of Bimala in Ghare-Baire (The Home and the World), to analyze his evolving depiction of the "New Woman." Tagore's works serve as an artistic reflection of societal transformations in early 20th-century Bengal, where traditional gender roles were questioned. Through Bimala, Tagore examines the complexities of female identity, autonomy, and agency within a patriarchal framework. This paper discusses how Tagore’s literary vision, along with his own progressive stance on women’s rights, underscores his portrayal of female empowerment as both liberating and challenging.

Keywords

Rabindranath Tagore, New Woman, Bimala, gender roles, Bengali literature, feminism, Ghare-Baire, early 20th century

Introduction

Rabindranath Tagore, one of India’s most revered literary figures, often questioned the conventions of his time, particularly concerning gender and social norms. His works, notably Ghare-Baire (The Home and the World), reveal his deep concern for women's empowerment and autonomy. Tagore’s portrayal of Bimala as a "New Woman" epitomizes his progressive view on female agency. As Tagore once remarked, “The highest education is that which does not merely give us information but makes our life in harmony with all existence.” This sentiment resonates in Ghare-Baire, where Bimala’s journey reflects the struggle of Bengali women of the era to harmonize traditional roles with the promise of self-realization and independence.

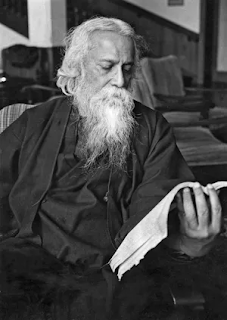

About the Rabindranath Tagore :

Rabindranath Tagore (born May 7, 1861, Calcutta )

He was a Bengali poet, short-story writer, song composer, playwright, essayist, and painter who introduced new prose and verse forms and the use of colloquial language into Bengali literature, thereby freeing it from traditional models based on classical Sanskrit.

He was highly influential in introducing Indian culture to the West and vice versa, and he is generally regarded as the outstanding creative artist of early 20th-century India. In 1913 he became the first non-European to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Rabindranath Tagore was the youngest son of Debendranath Tagore, a leader of the Brahmo Samaj, which was a new religious sect in nineteenth-century Bengal and which attempted a revival of the ultimate monistic basis of Hinduism as laid down in the Upanishads.

He also started an experimental school at Shantiniketan where he tried his Upanishadic ideals of education.

Tagore had early success as a writer in his native Bengal. With his translations of some of his poems he became rapidly known in the West.

Rabindranath Tagore's "Ghare-Baire" (The Home and the World) is a profound exploration of the complex dynamics between personal freedom and social responsibility. At the center of this narrative is Bimala, a figure that embodies the quintessential "New Woman" of early 20th-century India.

Bimala in Ghare-Baire: Tagore’s New Woman Relocating the “World in Her Home”

Bimala: The New Woman Archetype

Bimala emerges as a character representative of changing societal norms. The concept of the "New Woman" during Tagore's time was characterized by a blend of traditional values and a growing awareness of personal autonomy. She is introduced in a patriarchal household, where her world is dominated by the confines of home and the expectations of wifely duties. However, even within this restricted space, Bimala's spirit is restless, eager to engage with ideas beyond her domestic life.

Banerjee emphasizes that Bimala's character is not just a passive reflection of societal changes but an active participant in her own transformation. Her relationships with her husband, Nikhil, who embodies progressive ideals, and Sandip, a nationalist leader who captivates her with his charisma, serve as catalysts for her growth. This duality represents the dichotomy of tradition and modernity, as Bimala fluctuates between her roles as a devoted wife and an individual seeking her own identity.

Bimala, the protagonist of Rabindranath Tagore's novel Home and the world , stands as a compelling representation of the "New Woman" archetype emerging in the early 20th century. This concept encapsulates the tension between traditional gender roles and the burgeoning desire for personal autonomy and self-expression among women. In the context of Tagore's time, the "New Woman" symbolized a shift in societal norms, where women began to challenge the confines of domesticity and seek a more active role in both the public and private spheres.

Bimala's Background and Context

Bimala is introduced within the confines of a patriarchal household, where her existence is largely defined by her duties as a wife. The societal expectations placed upon her emphasize submission, obedience, and the nurturing of her family. However, Tagore paints Bimala as a character whose spirit is restless and eager for intellectual and emotional engagement beyond the limitations of her domestic life. This restlessness is indicative of the broader changes occurring in society, where women began to question their roles and seek greater independence

“For we women are not only the deities

of the household fire,

but the flame of the soul itself.” (Tagore)

The Dichotomy of Relationships

Bimala's relationships with two pivotal male characters, her husband Nikhil and the charismatic nationalist leader Sandip, serve as critical catalysts for her personal transformation. Nikhil represents progressive ideals and embodies a modern approach to marriage, encouraging Bimala to think independently and engage with the world around her. His support for her education and intellectual pursuits signifies a departure from traditional norms, allowing Bimala to explore her identity beyond the confines of her domestic role.

In contrast, Sandip represents the allure of nationalism and the passionate call for action. His charisma and fervor captivate Bimala, drawing her into a world of political engagement and fervent nationalism. This relationship symbolizes the tension between tradition and modernity, as Bimala oscillates between her loyalty to Nikhil and her attraction to Sandip's passionate ideals.

The Journey of Self-Discovery

Bimala's journey is one of self-discovery, where she grapples with her identity as a wife, a nationalist, and an individual. As she navigates her relationships with Nikhil and Sandip, Bimala confronts the complexities of her desires and the societal expectations placed upon her. This internal conflict is emblematic of the broader struggles faced by women of her time, as they sought to carve out a space for themselves in a rapidly changing world.

Tagore's portrayal of Bimala reflects a nuanced understanding of the challenges faced by women in the early 20th century. Her character embodies the duality of tradition and modernity, as she navigates the expectations of her roles while striving for personal autonomy. Ultimately, Bimala’s evolution signifies the potential for women to assert their identities and challenge societal norms, making her a pivotal figure in the discourse on gender and identity.

Bimala’s Internal Conflict and Transformation

Bimala's character in Rabindranath Tagore's Gora serves as a poignant representation of the internal struggles faced by women during the tumultuous nationalist movement in early 20th-century India. Her journey is emblematic of the broader societal challenges women encountered as they attempted to navigate the competing demands of tradition and modernity. Central to her character is a profound internal conflict that embodies the clash between her personal desires and societal expectations.

The Duality of Relationships

Bimala's relationship with her husband, Nikhil, is rooted in mutual respect and intellectual companionship. Nikhil is portrayed as a progressive figure, encouraging Bimala to embrace her education and cultivate her individuality. He represents a more modern approach to marriage, where emotional and intellectual bonds are prioritized over traditional gender roles. However, this relationship is sharply contrasted by Bimala’s fascination with Sandip, the charismatic nationalist leader whose fervent and fiery rhetoric captivates her senses. Sandip embodies the allure of change and rebellion, drawing Bimala into the passionate world of activism and national pride.

This duality of relationships highlights Bimala's internal turmoil. On one hand, she feels a sense of loyalty and obligation toward Nikhil, who supports her growth and understanding of the world. On the other hand, she is enticed by Sandip's revolutionary zeal, which ignites her emotions and evokes a longing for agency that she has not previously experienced. The emotional conflict between duty and desire reflects a broader societal tension—the struggle between the ideals of nationalism and the traditional roles formatted for women in Indian society.

As Banerjee observes, "Bimala’s initial fascination with Sandip's fervor represents not just a personal attraction but also an awakening to her own latent aspirations" (Banerjee 8). This comment underscores the significant transformation Bimala undergoes as she grapples with her identity and agency against the backdrop of a changing India.

The Journey of Transformation

Tagore effectively captures the complexities of Bimala's emotions, demonstrating her evolution from a naïve and passive character to a woman who begins to recognize her own desires and the implications of her choices. Initially drawn to Sandip's radical ideas, Bimala is swept away by the excitement and fervor of nationalism. However, as she becomes more involved in this world, she starts to confront the reality of her motivations and the ethical dilemmas her newfound passion brings.

Her internal conflict culminates in a pivotal moment of realization—Bimala understands that her loyalty to Nikhil does not negate her agency as an individual. The struggle she faces leads her to a deeper understanding of herself, ultimately allowing her to redefine the parameters of her identity. Banerjee highlights this pivotal transformation, stating that "Bimala's journey from attraction to realization signifies her emergence as an active participant in her life, capable of making choices that reflect her true self" (Banerjee 10). This transformation is significant not just for Bimala as an individual but also serves as a metaphor for the awakening of women’s agency during a critical period in India's history.

Bimala's internal conflict and subsequent transformation reflect the complexities faced by women in a society grappling with notions of nationalism and identity. Through her journey, Tagore articulates the need for women to assert their agency within societal constraints, allowing their voices to be heard. Bimala's evolution from passivity to active decision-making embodies the broader struggle for women to reclaim their identities amid changing social landscapes.

The Relocation of the “World in Her Home”

In Rabindranath Tagore's Gora, the motif of home serves as a crucial element in the narrative, encapsulating Bimala's inner conflict and societal constraints. The home is portrayed not merely as a physical space but as a profound metaphor for the restrictions imposed on women in a patriarchal society. Initially, Bimala views her domestic environment as a sanctuary, a space where she is cared for, respected, and safeguarded from the chaos of the outside world. However, as the narrative unfolds, this perception shifts dramatically; the home transforms into a metaphorical prison that confines her desires and aspirations, limiting her potential for growth and self-exploration.

The Sanctity of Home vs. Its Confinement

At the outset of the story, Bimala takes pride in her role within the household, derived in part from the expectations established by her traditional upbringing. Her relationship with her husband, Nikhil, is based on mutual respect and understanding, with Nikhil encouraging her to cultivate her intellect. Banerjee observes that “Bimala begins to find a sense of fulfillment within the confines of her home as she engages in intellectual discussions with her husband” (Banerjee 3). This sense of security, however, belies the underlying tensions surrounding her identity as a woman caught between conventional norms and the burgeoning nationalist sentiments of the time.

As Bimala interacts with the outside world—primarily through her encounters with Sandip, a nationalist leader—her understanding of home undergoes a radical transformation. Sandip's passionate rhetoric and revolutionary zeal awaken a dormant desire for agency within Bimala, prompting her to question the restrictive nature of her domestic life. In doing so, she recognizes that the same walls that once offered her comfort can also confine her spirit. Tagore adeptly illustrates this paradox, demonstrating how Bimala's domestic sanctuary evolves into a site of struggle and disillusionment.

The Crumbling Walls of Tradition

Bimala's realization that her home limits her potential is both painful and liberating. The intrusion of nationalist ideologies into her life forces her to confront the traditional roles imposed upon her, leading to a gradual awakening. As she becomes increasingly captivated by Sandip's worldview, Bimala’s internal conflict intensifies. The values of loyalty to her husband clash with her growing desire for independence, creating a tension that reverberates throughout the narrative.

“I am willing to serve my country; but my worship I reserve for Right which is far greater than my country. To worship my country as a god is to bring a curse upon it.”

— The Home and the World

This tension is further explored by Banerjee, who states, "The crux of Bimala's conflict lies in her simultaneous longing for belonging and her yearning for self-actualization, a duality that complicates her relationship with both her home and her family" (Banerjee 6). This complexity underscores the significant cultural shifts occurring during Tagore's time, where traditional women's roles faced challenges from emerging feminist ideas and nationalist sentiments, urging women to reclaim their identities outside the domestic sphere.

A Broader Symbol of Change

Ultimately, Bimala's journey signifies a broader commentary on women's roles within society. The home, once a symbol of stability, becomes a contested space where Bimala grapples with her identity and her newfound awareness of herself as a woman with desires and ambitions beyond the domestic realm. Tagore poignantly captures this struggle, illustrating how societal changes influence personal transformations, prompting Bimala to recognize that the "world" can exist outside her home—a world teeming with possibilities yet fraught with conflict.

As Bimala's understanding of home evolves, it encapsulates the transformational journey of women in the nationalist movement—a process marked by conflict, confusion, and ultimately, empowerment. The metaphor of relocating her “world” signifies not just a personal awakening but also a collective one, as women begin to assert their presence and agency in spaces previously dominated by men.

The Dual Nature of Home

For Bimala, the home serves as a complex embodiment of traditional gender roles, relegating her to the status of a dutiful wife whose existence is primarily defined by servitude and fidelity. In the context of Rabindranath Tagore's Gora, this domestic space becomes a significant site of internal conflict, as Bimala grapples with the expectations imposed upon her by a patriarchal society, which dictate that her primary identity should revolve around being a caretaker and supporter of her husband, Nikhil. Initially, she internalizes these societal norms, leading her to believe that her happiness and fulfillment are intrinsically tied to her domestic responsibilities. Tagore artfully depicts these tensions, emphasizing how Bimala's understanding of her role is shaped by the cultural constraints surrounding her. Her initial compliance indicates not just personal subjugation but a broader commentary on the limited roles afforded to women in her society.

Despite her outward acceptance of these traditional roles, Bimala’s sense of self begins to destabilize as she engages with rebellious ideologies. Her interactions with the world outside her home—most significantly through her encounters with Sandip, a charismatic nationalist leader—serve as a turning point. Sandip represents a vibrant world marked by political engagement, personal autonomy, and the promise of liberation from domesticity. His compelling persona and fiery ideals ignite a sense of longing and desire within Bimala, prompting her to reconsider her identity beyond the confines of her home. As Banerjee notes, "Bimala's interactions with Sandip act as a catalyst for her awakening, challenging her previously held notions of duty and loyalty" (Banerjee 4).

The Impact of External Influences

Bimala's awakening arises amid the nationalist fervor that permeates the sociopolitical landscape of Tagore's India. This burgeoning awareness leads her to confront the contradictions in her life; while her home offers a sense of security, it simultaneously acts as a constraining force on her individuality. In the face of Sandip's revolutionary fervor, Bimala recognizes the dissonance between her passionate aspirations and her prescribed domestic role. The "world in her home" becomes increasingly suffocating as she longs for a more expansive identity that includes her own desires and ambitions.

As Bimala navigates her feelings towards Sandip, Tagore explores the complexities of her emotional landscape. She experiences a pulsating pull between her loyalty to Nikhil and her attraction to the ideas that Sandip espouses. This dichotomy serves to highlight the dual nature of home—it can provide comfort and stability while also stifling one’s growth and sense of self. Bimala’s internal struggle exemplifies the profound societal transitions occurring at that time, where women began to assert their rights to self-definition in a rapidly changing environment.

Banerjee further elucidates this conflict, emphasizing that "Bimala's burgeoning sense of self challenges the very foundation of her marital loyalty and forces her to confront the limitations that have been placed upon her by tradition" (Banerjee 6). This sentiment captures the essence of her transformation—she comes to recognize that her loyalty and identity need not be limited to the domestic sphere but can evolve in tandem with her personal growth and understanding of national identity.

Through Bimala's character arc, Tagore addresses the complexities of women's identities within a patriarchal society, ultimately advocating for an expanded notion of self that transcends the boundaries of the home. The dual nature of home—to be both a sanctuary and a prison—serves as a powerful metaphor for Bimala's struggles, reflecting the broader dynamics of gender, autonomy, and revolutionary thought during a pivotal time in history. Her journey signifies not only personal transformation but also a collective awakening among women, urging them to seek fulfillment beyond the expectations historically imposed upon them.

The Clash of Loyalties

As Bimala's world begins to enlarge, she finds herself embroiled in a tumultuous struggle between conflicting loyalties that challenge her understanding of identity and belonging. Her commitment to Nikhil, who embodies progressive ideals and actively encourages her intellectual pursuits, stands in stark contrast to her growing fascination with the nationalist cause championed by Sandip. This tension between two powerful influences in her life creates an emotional battleground, as Bimala grapples with her aspirations and conflicting desires. The home, once thought to be a stable presence in her life, transforms into a site of internal conflict where her sense of self is continually contested.

“The real freedom is not outside ourselves.

The fetters are within our own mind and spirit.”

— Ghare-Baire (The Home and the World)

In her article, Banerjee elaborates on this conflict by stating, "Bimala's journey illustrates the larger theme of women negotiating their identities within the constraints of societal norms, as the pull of the outside world challenges her loyalty to the home" (Banerjee 5). This statement encapsulates the essence of Bimala's struggle, as she navigates the complexities of her dual roles. On one hand, she is a devoted wife, dutifully fulfilling the expectations placed upon her by tradition; on the other, she is an emerging individual who seeks agency and autonomy in a world that invites her to expand her horizons. This internal conflict manifests in profound emotional turmoil, as Bimala attempts to reconcile these competing identities.

Bimala's interactions with Sandip serve as a catalyst for her awakening, igniting a desire for a life beyond domesticity. Sandip's passionate rhetoric and charismatic presence challenge her to envision a reality where she is not merely defined by her relationships but is instead an active participant in the socio-political landscape. As she becomes increasingly drawn to Sandip's ideals, Bimala is forced to confront the implications of her choices. The loyalty she feels towards Nikhil, who represents a more progressive and nurturing vision of womanhood, is put to the test as her fascination with Sandip’s revolutionary fervor grows stronger.

Tagore poignantly captures Bimala's emotional struggle, illustrating how the clash of loyalties creates a profound sense of dislocation within her. Her eventual realization that the "world" exists beyond the confines of her home signifies a critical moment of self-awareness and enlightenment. This awakening is not merely personal; it reflects the broader movement for women's agency during the socio-political upheaval of Tagore's time. As Bimala begins to recognize the potential for self-definition outside the traditional roles assigned to her, she embodies the aspirations of many women who sought to break free from the limitations of their circumstances.

Furthermore, Banerjee emphasizes that "the complexity of Bimala’s character lies in her ability to navigate these conflicting loyalties, ultimately leading her to a more nuanced understanding of her identity" (Banerjee 6). This navigation is fraught with difficulty, as Bimala must contend with societal expectations that dictate her behavior while also grappling with her burgeoning desire for independence. Tagore’s portrayal of her journey serves as a powerful commentary on the evolving roles of women in a rapidly changing society, where the struggle for agency is often met with resistance from both within and outside the home.

Through Bimala's experiences, Tagore invites readers to reflect on the complexities of women’s identities in a changing society. The clash of loyalties she experiences highlights the broader societal tensions faced by women during this period of transformation. Bimala's journey is emblematic of the struggle for self-assertion and the quest for a voice in a world that often seeks to silence it. Ultimately, her expansion of worldview represents not just her personal growth but also a collective awakening among women, signaling a shift towards greater agency and autonomy in the face of traditional constraints.

The Role of Nationalism and Gender Politics

Ghare-Baire is not only a tale about an individual but also serves as a profound reflection of the larger socio-political context of early 20th-century India. The interplay between nationalism and gender politics is vital to understanding Bimala's character and her experiences within the confines of her home. At the heart of this narrative is the figure of Sandip, who embodies an aggressive nationalism that demands a deep sense of duty towards the nation. This sense of duty clashes with Bimala's domestic responsibilities and traditional roles as a wife, leading to a significant internal struggle. This tension raises critical questions about the role of women in the nationalist movement and the complexities of their involvement in the political landscape of the time.

Through Bimala, Tagore critiques the masculine politics of nationalism, which often overlook and minimize the contributions and sacrifices of women. Nationalist movements, particularly those driven by male leaders like Sandip, tend to define engagement and loyalty in terms of combat and action, sidelining the essential, albeit less visible, contributions of women. Banerjee’s analysis underscores this point, emphasizing that "Bimala’s struggle within her home symbolizes the struggles of Indian women as they negotiate their identities in a rapidly changing society" (Banerjee 7). Bimala's domestic conflict can be seen as emblematic of the broader societal tension that women faced during this period, where their roles were often relegated to the private sphere, despite their potential for engagement in public life and social change.

The domestic sphere, once viewed solely as a place of limitation and confinement for women, gradually transforms into a site of revolution as Bimala seeks to harmonize her personal aspirations with her societal obligations. Tagore crafts a narrative that challenges conventional notions of femininity, suggesting that women's empowerment can arise from their unique position within the home. Instead of merely accepting their roles, women like Bimala engage with the political ideals of nationalism, asserting their importance in the larger struggle for independence and identity.

Moreover, the novel reveals that the intersection of nationalism and gender politics creates a complex dynamic where Bimala's relationship with Sandip represents both a source of liberation and a chain of dependence. His passionate political zeal enthralls her, yet it simultaneously demands a level of allegiance that conflicts with her loyalty to Nikhil, who represents a gentler, more progressive vision of gender relations. Banerjee notes that "the rift in Bimala's loyalties—her admiration for Sandip's spirited nationalism versus her commitment to Nikhil's nurturing idealism—forces her to negotiate her identity in a landscape dominated by masculine discourse" (Banerjee 8). This negotiation highlights the struggles women's voices face in political dialogues and emphasizes the need for a more inclusive nationalism that recognizes and values female perspectives.

Bimala's journey illustrates the challenges of reconciling personal desires with the collective aspirations of a nation seeking freedom from colonial rule. As she navigates her relationships and confronts her own beliefs, she becomes a representative of the aspirations of countless women who yearn for agency and recognition within the nationalist framework. Tagore's narrative ultimately suggests that the path to empowerment for women is not a rejection of their domestic roles but rather an integration of these roles into a broader understanding of national identity and social responsibility.

The exploration of nationalism and gender politics in Ghare-Baire challenges readers to reconsider the implications of traditional roles and the necessary space for women's voices within the nationalist movement. Bimala's character metamorphoses from a symbol of domesticity to one of revolutionary potential, revealing the intricate relationship between personal agency and collective identity. By portraying the complexities of women’s experiences in the nationalist struggle, Tagore advocates for a redefined understanding of nationalism—one that inclusively celebrates the contributions of women and recognizes their fundamental role in shaping the future of a nation.

Bimala’s Agency and Empowerment

Ultimately, Bimala's journey can be seen as a profound exploration of empowerment and self-discovery. Throughout Ghare-Baire, as she confronts the complexities of her relationships with both Nikhil and Sandip, as well as the broader socio-political landscape of early 20th-century India, Bimala makes choices that reflect her evolving identity and growing sense of agency. The culmination of her character arc is strikingly marked by her rejection of Sandip’s aggressive nationalist ideals. Through this rejection, she recognizes that true empowerment lies not in embracing tumultuous nationalism—which often marginalizes women's voices and experiences—but rather in understanding and prioritizing her own needs, values, and aspirations.

As Banerjee asserts, "Bimala’s final choices illustrate a significant shift in her consciousness, moving from passive acceptance of her roles to an active engagement with her identity and desires" (Banerjee 9). This transformation is critical, as Bimala acknowledges her responsibilities not just to her husband and her home but also to herself, further emphasizing the multifaceted nature of her identity as a woman in a changing society. This self-awareness marks a departure from traditional notions of womanhood, which often confine women to the domestic realm without recognition of their individuality and autonomy. By asserting her own priorities and desires, Bimala paves the way for a more nuanced understanding of female agency—one that is not limited to the confines of societal expectations.

The significance of Bimala’s journey lies in her realization that the world has intruded upon her home—both literally and metaphorically. The fusion of her domestic life with the socio-political upheaval around her allows her to redefine her place within it. Tagore illustrates this transformation through Bimala’s internal struggle, as she balances her emotional attachments with the radical ideas brought forth by Sandip, which initially captivated her. However, as she grows more self-aware, she rejects the notion that her value is tied solely to her loyalty to the nationalist cause as represented by Sandip. Instead, she starts to cultivate a sense of self that transcends the expectations placed upon her by patriarchal society.

In her final moments of clarity, Bimala recognizes that empowerment does not come from aligning herself with a singular nationalistic cause but from embracing her complex identity as a woman who can engage critically with both her personal relationships and the societal demands surrounding her. The world outside her home, which once seemed a symbol of turmoil and conflict, becomes a space of possibility where she can assert her voice and challenge the diluted representation of women in nationalist discourse.

Moreover, Banerjee further emphasizes that "Bimala's journey is not simply about rejecting one form of identity for another, but about integrating her experiences into a cohesive self that can navigate the complexities of her existence" (Banerjee 10). This statement captures the essence of Bimala’s empowerment; she actively engages with the contradictions and complexities of her identity, ultimately finding strength in her multifaceted nature.

Bimala’s character arc serves as a powerful commentary on the intersection of gender and nationalism, revealing the intricate dynamics of female empowerment in a rapidly changing socio-political landscape. Through her journey of self-discovery and agency, Tagore advocates for a more holistic understanding of womanhood—one that embraces both the personal and the political. As Bimala reclaims her identity and asserts her autonomy, she emerges not only as a symbol of personal empowerment but also as a beacon for women as they navigate the challenges of identity and agency in a world that often seeks to define them.

In continuum, to explore Tagore’s rewritten epic of a woman (epitomized in real life as the New Woman), we need to reflect on Tagore’s shaping of the image of the New Woman particularly in his rewriting of Sita imaging as Bharatmata. By skilfully portraying Bimala’s struggle as an “epic battle” Tagore consciously evokes the The Ramayana, casting Bimala in the role of Sita, Nikhil in the role of Rama and Sandip in the role of Ravana. Sita in The Ramayana and Bimala in The Home and the World are allegorically categorized with specific Hindu construction of women either as the agent of change, of reform or of revolution. Both of them represent an iconographic presentation of various phenomenal forms of feminine divinity; the mythic icon and the patriotic emerging from the symbolism invoking the feminine principle as the source of creation, destruction and restoration. Like Bimala, Sita in the epic The Ramayana begins her life -journey as a typical bride: tender and loving by her nature, bethrowed to her husband’s care and concern twice ‘as much as he loved her’. She could have coated forever in the land of heritage unless trouble had not intervened her path. Her first crisis initiates through her assertion to accompany Rama in exile, challenging the traditional norms of the Ayodhya Nagar worshipping women behind the screens as purdah nashin. Allegorically in Ghare- Baire Nikhil citing Sita and Draupadi as examples of ‘free women’ draws an analogy with Bimala in her to encounter with the world not to be keep herself as purdah nashin but to allow her to accompany him to Calcutta to complete his M.A. degree. He urges Bimala to know “come into the heart of the outer world and meet reality” (Tagore GB,18) “The greedy man who is fond of his fish stew has no compunction in cutting up the fish according to his need. But the man who loves the fish wants to enjoy it in the water; and if that is possible, he waits on the bank; and even if he comes back home without a sight of it he has the consolation of knowing that the fish is all right. Perfect gain is the best of all; but if that is impossible, then the next best gain is perfect losing.” (Tagore THW, 84)

Thus, both Sita and Bimala leaving the inner circles of the zenana come to the ‘outer world’ equating the terms of their ‘free living’ with the needs of their individual existence. However, it can never be ignored that both could have stayed in their confinement, had not the inspiration or the initiation remained on the part of their husbands. Thus, counteracting the traditional custom of remaining within the lakshmanrekha of their home bounds, their first moves into the “world” reinforce their statements of individuation promoted and protected by their male counterparts at large.

In "Ghare-Baire," Tagore presents Bimala as a complex character straddling the line between tradition and modernity. As analyzed by Ayanita Banerjee, her journey embodies the struggles of women during a transformative time in India’s history. Bimala’s evolution from a dutiful wife to a self-aware woman who grapples with the realities of her world is a testament to Tagore’s nuanced understanding of gender, nationalism, and personal agency.

Bimala's story reinforces the idea that a woman’s home can be a site of empowerment and transformation. By relocating the “world in her home,” she not only challenges the boundaries set by society but also asserts her place in the narrative of nation-building. Tagore's portrayal of Bimala resonates with contemporary discussions on female identity, agency, and the intricate interplay between personal and political spheres, capturing the essence of what it means to be a woman navigating a changing world.

Words : 5565

Images : 3

Works Cited

Banerjee, Ayanita. “Bimala in Ghare-Baire: Tagore’s New Woman Relocating the ‘World in Her Home.’” Academia.edu, www.academia.edu/62782312/Bimala_in_Ghare_Baire_Tagore_s_New_Woman_Relocating_the_World_in_Her_Home_. Accessed 27 Nov. 2024.

Banerjee, Ayanita. “Bimala in Ghare-Baire: Tagore’s New Woman Relocating the ‘World in Her Home.’” Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, vol. 13, no. 3, 2021, pp. 1–10. www.rupkatha.com/V13/n3/v13n337.pdf. Accessed 27 Nov. 2024.

Kathpalia, Bhuvi. The figure of the “New Woman” in Twentieth Century Bengal: A Study Based on Selected Novels of Rabindranath Tagore and Their Later Cinematic Adaptations, https://tiss.academia.edu/BhuviKathpalia.

Kumar, Radha. The History of Doing: An Illustrated Account of Movements for Women’s Rights and Feminism in India, 1800–1990. Academia.edu, www.academia.edu/69370578/The_history_of_doing_An_illustrated_account_of_movements_for_womens_rights_and_feminism_in_India_1800_1990. Accessed 27 Nov. 2024.

“Rabindranath Tagore.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2024, www.britannica.com/biography/Rabindranath-Tagore. Accessed 27 Nov. 2024.

Comments

Post a Comment